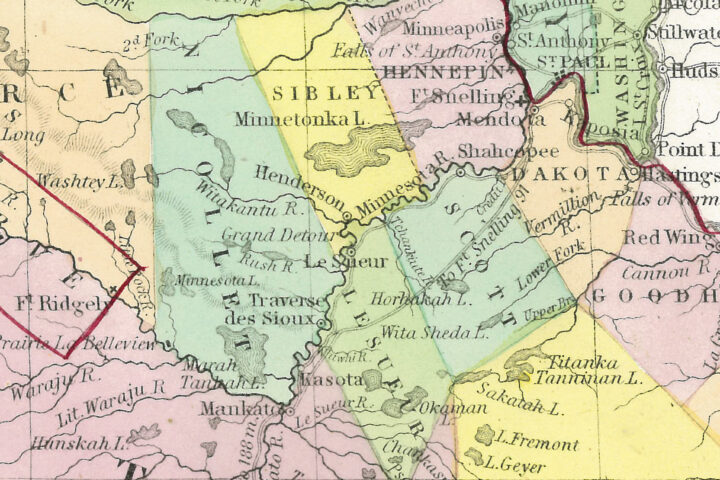

The Minnesota River valley was formed about 13,000 years ago when Lake Agassiz broke through a barrier at Big Stone Lake on the border with South Dakota. The result was the largest freshwater lake in North America suddenly draining south through what must have been a depression or existing shallow valley created by earlier glacial melting. As the flow roared past the eventual site of Mankato, it turned north due to a bedrock obstruction racing to the current city of St. Paul where it joined the Mississippi drainage system. The rapid drainage carved a river valley through glacial deposits two to four miles wide and hundreds of feet deep. After the lake drained, the scoured-out valley allowed the remaining much smaller river to meander back and forth in the valley for over 10,000 years, regularly changing its bed location, especially in times of flooding.

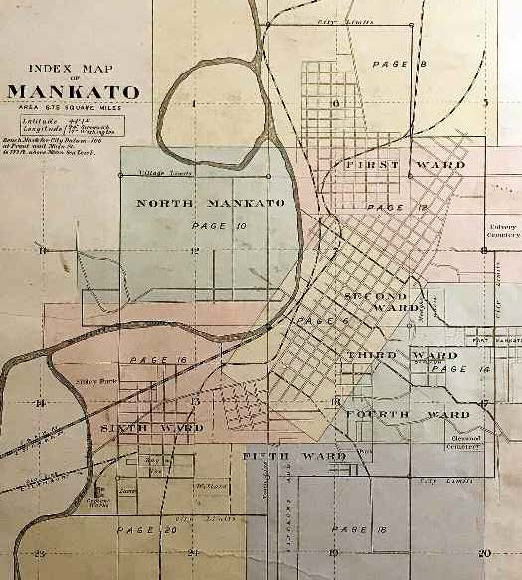

Early white settlers found a river with twists and bends all along its course, and still subject to intermittent changes in bed location. In the 1850’s Mankato was laid out on the southern side of the great bend in the river and North Mankato on the north bank. An additional great loop in the river occurred just north of both cities and the land contained in that loop on the Mankato side of the river was called “Lowertown” because its elevation was the lowest spot on the Mankato side of the river. (see map) Composed mostly of mud flats, sand, and clay, and overgrown with willows and wild grape vines, and clearly within the river flood plain, it was considered wasteland and not suitable for building. With the exception of the clay once mined there for soft brick, Lowertown was of little value to anyone in the last quarter of the 19th century.

On the North Mankato side, the great loop of the river ran along what is now the north end of Lake Street and then turned east, a block north of Webster Avenue. (see map) The early steamboats coming down to Mankato from St. Paul knew that when they came to Jefferson’s Bend (so named from the stone Jefferson House standing on a bluff above the river’s east side), it meant that just one last loop of the river, around lower town, would bring them to the docks in Mankato near the present site of the old Hubbard Mill. As it made this loop, steamboats passed right along the bluff only a few yards from current Lake Street in North Mankato. The oxbow lake along the street is the remnant of that old river loop.

Over the last century and a half, there have been intermittent discussions about North Mankato joining with its sister city across the river. One of the more interesting suggestions in the early 1900s involved connecting the loop of the river along Lake Street to the Minnesota River at Cumming’s Landing (Now Sibley Park) by digging a connection along the base of Lake Street.

This would have brought the river directly in front of the then Nicollet County Commissioner Chairman Wendel Hodapp’s house, dividing the rest of his property stretching from Lake Street to the river, from his house, an event he would probably have looked upon with disfavor. Nothing ever came of the proposal. It would have also put most of the current lower North Mankato in Blue Earth County and eliminated the need for any bridge at Main Street.

One of the major floods, common to the meandering Minnesota River, happened in 1908 and complicated the unification issue. The flood changed the river’s course yet again, cutting off the loop north of the city and changing the river boundary between the two cities without human intervention. The dike constructed along Webster Avenue slowed the river current, causing it to back up to the north. This caused the main current to cut a new and straighter channel where it flows today. The remaining cut-off portion of the Minnesota River became an oxbow lake on the North Mankato side as the river’s main channel moved to the east. This resulted in the strange situation of part of Blue Earth County, formerly known as Lowertown, to be located in what should be, based on the new river boundary, in Nicollet County.

Mankato offered to transfer the title of Lowertown to North Mankato, but overtures were rejected. North Mankato evidently considered the marshy flood-prone ground to be worthless. For a number of years after that, North Mankato residents used the old river embankment past the Webster Avenue dyke at the end of Range Street as the place to dump their refuse.

The arrival of 4-lane highway 169, which followed the new river course, created a new dike out of its elevated roadbed. The once useless lower townsite suddenly had economic value. Commercial enterprises developed along a highway service road with tax revenue going to Mankato instead of North Mankato. Based on the pre-stream capture maps, only the old Best Western Hotel, the North Mankato City Garage, and several businesses along Webster were still on the Mankato side of the river. Traveling north on Lake Street past Webster Avenue, the houses on the left are in North Mankato, but the land on the right side of the road is in Mankato. The remnants of the old river bed are still visible as the oxbow at the north end of Lake Street.

With a new interchange with Highway 169 being planned and the re-development of the old Best Western site into commercial and residential use, the old Lowertown political exclave is suddenly primed for development by Mankato. Much of the new tax revenue will find its way into Mankato coffers. Despite its meandering history, the Minnesota River is not likely to change course in this part of the river valley again any time soon. With increasing tax revenue generated in historic Lowertown, Mankato’s old offer from the turn of the century to transfer Lowertown to North Mankato is off the table.